Confused about the filibuster? Here's how it works and why some want to end it

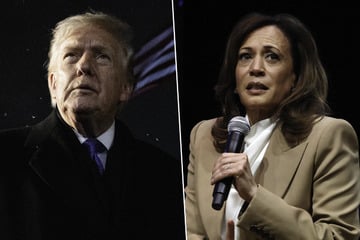

Washington DC - Democrats' attempts to pass national voting reforms have placed the filibuster under even greater scrutiny.

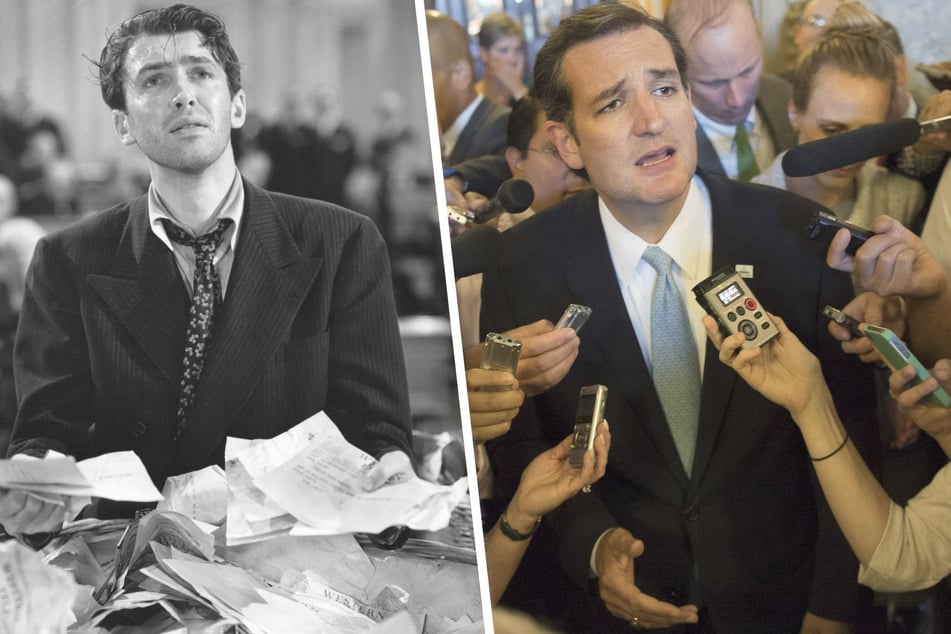

The term "filibuster" may conjure images of exhausting and never-ending speeches on the Senate floor. Remember in 2013 when Texas Senator Ted Cruz started reading bedtime stories to his kids on live TV? Not exactly prime-time content.

Or it may remind movie buffs of Jimmy Stewart's impassioned defense of a national boys' camp in the 1939 classic Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

But the filibuster's power to derail policy proposals doesn't always involve such public and cringeworthy displays. Just the threat of a filibuster is often enough to stop proposed legislation in its tracks.

So how exactly does it work?

For a bill to pass the Senate, it must go through several steps. After it's brought to the floor, senators have a chance to engage in debate. The senators must vote to end the debate before they can vote on whether to pass the bill itself.

The tricky part comes with the first vote: while it only takes 50 senators to pass a bill, it takes 60 – a supermajority – to end debate. That rule has been in effect since 1917 and is referred to as a cloture vote. With an evenly split Senate like the one we have now, it is very difficult to muster the supermajority required in many cases to override a filibuster threat.

Rather than putting themselves through endless ramblings like Cruz's, many senators choose not to introduce bills if they already know they won't receive the 60 votes needed to end debate.

Data from the Senate website show the number of motions and votes related to filibusters has increased hugely.

In this way, the Senate rules give minority opinion-holders disproportionate influence in lawmaking – and they're increasingly taking advantage of that power.

Is there any way around the filibuster?

In some cases, the Senate can pass certain bills not subject to a filibuster with just 51 votes. This process, called reconciliation, applies to certain tax and budget bills. Congress usually only uses the process once for each fiscal year. It was used in 2021 to pass the Biden Administration's $1.9-trillion American Rescue Plan.

What exactly counts as "budgetary" legislation is also a tricky issue. The For the People Act, for example, can't be passed through reconciliation and is probably doomed, as it failed to win bipartisan support in the Senate.

The threat of filibuster has thrown a wrench in the bill's path through the upper chamber, even though the legislation has broad public support and would likely get the simple majority needed to pass.

That's why many Democratic senators and progressive activists are renewing calls to end to the filibuster, or more specifically, the required supermajority vote to end debate. Because getting the 60 votes required to eliminate the filibuster entirely seems unlikely, they will have to explore other options for removing or weakening the current procedure.

Cover photo: Collage: IMAGO / Cinema Publishers Collection, IMAGO / UPI Photo