New Yorker's brain surgery takes away the fear, but leaves much more behind

New York, New York - Jody Smith is a native New Yorker who – at first glance – seems like a "regular guy." He even has the New York accent and street smarts to prove it.

Yet, he's survived a rare event that has changed his life – for the better.

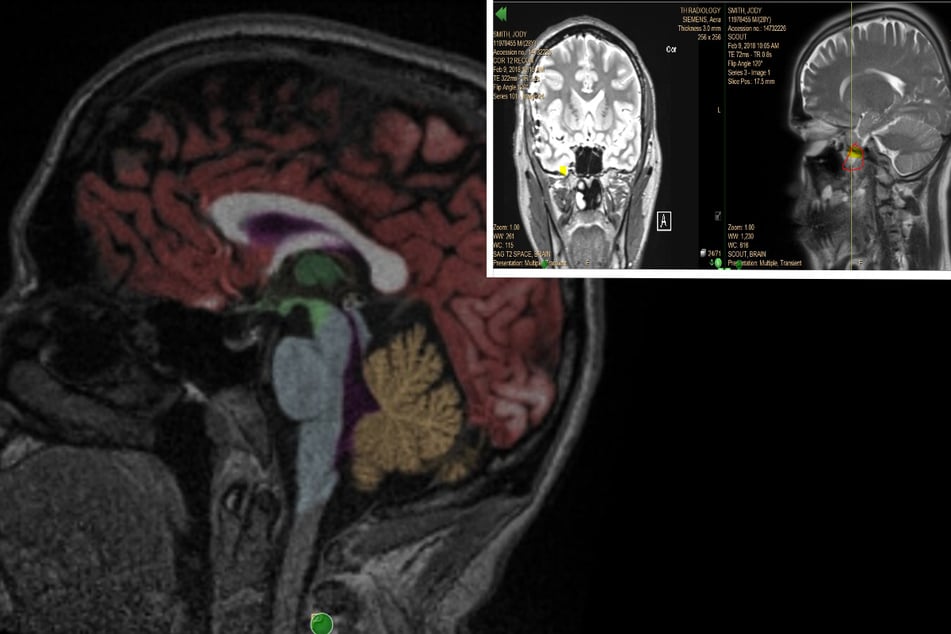

Smith has become somewhat of a phenomenon after a surgery to combat his epileptic seizures removed 10% of his brain.

After failed therapies, medications, and warnings that the consequences of his seizures could turn fatal, he decided to go under the knife.

He then became known by the media as "the man who feels no fear."

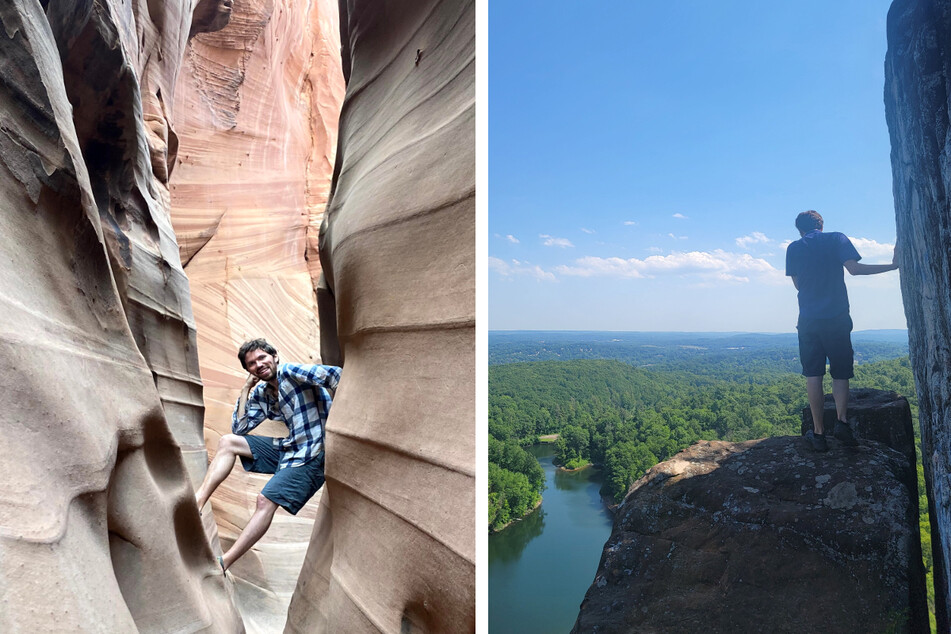

Post-surgery, Smith discovered a huge change in his emotional response to what most consider scary situations, and has tested the boundary between his mind and body with adrenaline-filled adventures.

His knees don't shake as much when he does via ferrata – cabled cliff climbing –and he says that he thinks "more logically" about his steps now, rather than being afraid he'll fall. It's a new type of confidence for the daredevil who dubs himself "unstoppable."

It's also caused him to become more of a chatterbox, which was great for our meeting in New York's Union Square Park.

The 32-year-old is a walking text book, and his own self-proclaimed "science project." He let TAG24 in on what he’s been through, and what he's learned.

The aftermath of his surgery has made him ponder the disconnect between emotions and how the brain works. He believes that an "overactive" brain is just like any other body part that can get injured, and might need some extra TLC.

"The revelation that I had was that the mind is more mechanical," he said. "You are not your brain."

It is an interesting thought: that emotions don't define someone's personality. Instead, they are produced by the brain independently – and they come and go. And when a part of your brain is removed, like Smith's, it might also remove some of the debilitating problems that can come with it.

"If I'm not my brain, who am I?" Smith recalled asking himself about his identity post-surgery. "What makes me, me?"

He has been on a mission to find out, and to empower others who might be asking similar questions.

"What matters to me is how I've touched people in a way that lets them see life differently or see themselves in a better way," Smith told me. "That feels really good."

Little did he know just how much his perspective would soon help someone else by a stroke of serendipity in the park.

"What makes me, me?"

"I thought we knew more about the brain than we do," Smith explained about his quest for knowledge about the human mind.

Since his health challenges began, the computer programmer has soaked in an astounding amount of medical information and learned how his surroundings affected him through trial-and-error.

We sat in Manhattan amidst the cacophony of passing sirens, thumping bass, and construction trucks that create the city’s symphony, just steps from the apartment he has lived in most of his life. Noisy neighbors were just one of the sounds that would regularly set off his epilepsy and trigger seizures. At one point, they were happening three times a day.

At first, Smith thought he was drinking too much coffee and "having a bit of anxiety here and there" – mostly, he says, over a fear of death. His seizures, caused by a presumed birth defect, were not the "convulsing on the floor" type. He'd experience 30 seconds of a feeling of "alertness" that something was going wrong, followed by an intense feeling of dread or sadness. He was only diagnosed when a larger seizure caused a severe lapse in memory.

Smith's "lightbulb" moment came with the removal of a piece of his right amygdala – a part of the brain that is responsible for emotional responses like fear and anxiety.

After his hospital stay, he began to subconsciously disassociate from many of the emotions he had before surgery. As he recovered, his fear of death no longer paralyzed him. In fact, the anxiety and fright was almost completely eliminated.

That's when he realized that "people tend to identify with their mental peculiarities, especially when they're considered deficiencies in society. So like, 'I am an anxious person. I am an angry person.'"

But now he believes these emotions don't necessarily translate to personality traits. Instead, they can be treated as stand-alone health issues, not ones that dictate who we are. He learned this first hand, as he no longer has the piece of his brain that was plaguing him and triggering his seizures.

"When I removed this tiny, four-centimeter piece [of my brain], and I no longer felt that [emotion of fear], it's gone," Smith explained. "It's much like if someone has a stomachache, they cut out their appendix, because that's what was causing the stomachache. It's gone. They weren't identifying with their appendix, but I was identifying with my amygdala."

He sees the realization that fears and anxieties are largely caused by excess activity in the brain as a key that can open doors to thinking differently about ourselves, and what we can control.

A chance encounter – and perhaps a sign

As the epilepsy survivor opened up to me with bubbling enthusiasm, we met a woman by coincidence who had a strangely similar story to Smith.

Overhearing our conversation, Jennifer sheepishly approached us and revealed that she herself had also been suffering from epileptic seizures for the last nine years.

She, too, is a candidate for brain surgery, and she is both hesitant and full of the emotion that Smith no longer has: fear.

"Would you mind if I described why I got surgery?" he asked her. "I don't have 10% of my brain."

It was an exchange that I watched in awe, and it proved that Smith is well on his way to achieving his goal of helping others.

Jennifer works as an interpreter, and has had trouble translating between languages as her speech and memory often lapse. She admitted she would most likely forget meeting us 10 minutes later.

Smith proceeded to rattle off statistics that show how the chances of memory loss, dangerous seizures, and even death can increase without the help of a surgery to get her condition under control. He also assured her she would be better for it, after recovering.

Jennifer told us she journals Bible verses, which she called her "lifers." She mediates on the glimmers of hope, and writes herself Post-it Note prayers that she sees when she wakes up.

It seemed ironic that Smith was now telling Jennifer to have faith.

"How did it feel at first, after the operation?" she asked him, wide-eyed.

"The second I woke up, I looked at my mom, and I said, 'Hey Mom. Tell everyone I'm ok.'''

Their meeting seemed to be a moment of synchronicity: simultaneous happenings without a casual connection that appear related, and are meaningfully intertwined.

Jennifer said she'd been praying for a sign – and that maybe crossing paths with Smith was it.

A new path

After Smith's surgery, it took over a year to heal and for his noise sensitivity to return to "normal."

Now he is able to listen to music, handle the commotion of the NYC streets, and go to loud concerts without feeling intimidated that the stimuli will bring on a seizure, as before.

Three years later, he has gone off of almost all of his meds, and despite some lingering problems with his memory, is "very happy" with where he is at. Most importantly, he is seizure-free.

What about his title as "The Man Who Feels No Fear"? Can we ever be truly fearless?

It might not be as clear-cut. Smith admitted that he still has some jitters, doubts, uncertainties, and "aversions." The difference is that he no longer has the piece of his brain where his seizures occurred – which is in the same part of the brain that could cause those emotions to take over his psyche.

And regardless of that removal, we all still have the part of our brain that triggers "fight or flight," the instinctual response to fear.

Yet Smith can now separate himself from his feelings, with the help of having a little less of his brain and a little more smarts.

"Find a path that is right for you," he advised those going through any type of mental challenge. "The world can help you. But I think that it's important to see [any mental struggle] as a problem that you have, rather than who you are."

Smith’s impulse to pass on the insight to others poured into our meeting of the minds, and into the chance encounter with Jennifer. He's hopefully inspired another fellow survivor.

His generosity might be the best result of his journey.

Cover photo: Collage: Courtesy Jody Smith & Lena Grotticelli