How Fukushima nuclear wastewater and colonial exploitation pose existential threat to Alaskans and Hawaiians

Geneva, Switzerland - Indigenous Alaskans and Hawaiian nationals are raising the alarm over the potential harms caused by wastewater released from Japan's Fukushima nuclear plant, which could worsen precarious environmental conditions resulting from generations of US colonial occupation.

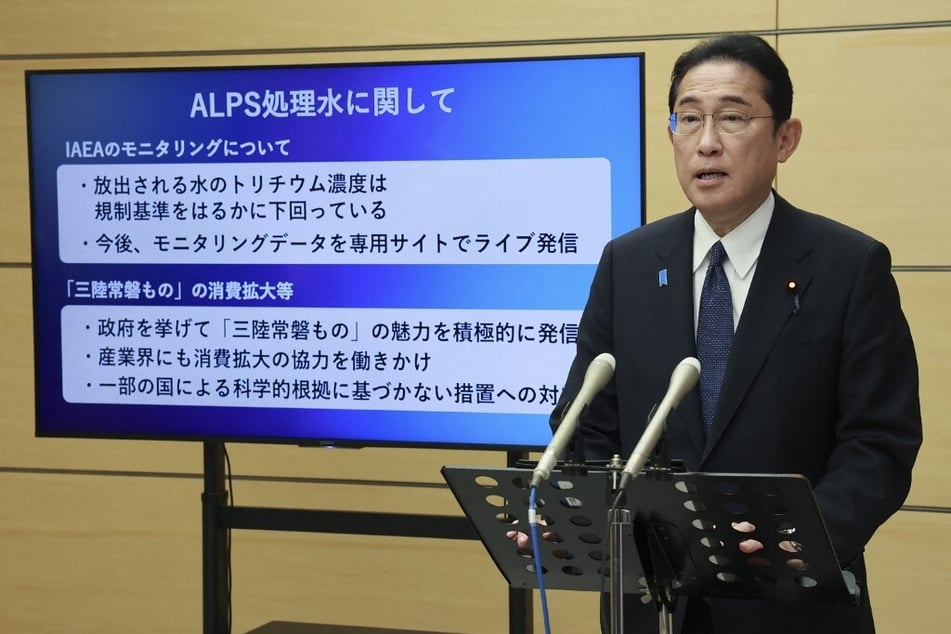

Japan has stoked controversy with its recent decision to release radioactive water from its Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the Pacific Ocean – just 12 years after the country experienced its worst-ever nuclear disaster following an earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

The Japanese government has already begun discharging the contaminated water. The release is set to take place in stages over 30 years, although experts warn it could take even longer.

The International Atomic Energy Agency has stated that the process meets safety standards and that the effects on people and the environment will be "negligible," but many scientists and impacted communities disagree. They argue there has not been enough research made available to assess the potential consequences.

Among those raising concerns are Hawaiian nationals and Indigenous Alaskans, who fear that ocean currents will carry the radioactive material to their waters and wreak havoc on local ecosystems and subsistence lifestyles.

"As protectors of this ocean, as the people who have lived here for millennia, we do not accept this kind of offhand declaration without any real proof or evidence that this is safe," His Excellency Leon Kaulahao Siu, foreign minister of the Hawaiian Kingdom, said during a Friday news conference at the Geneva Press Club.

"We just are outraged that this discharge of this contaminated water is going to affect all of us. It may be small at first, but it is going to affect all of us."

US colonialism drives environmental exploitation in Alaska and Hawaii

The potential devastation the Fukushima wastewater could unleash in Alaska and Hawaii would exacerbate conditions wrought by decades of United States occupation.

Alaska has been under US colonial rule ever since the government "purchased" the territory from the Russian Empire in 1867, despite Russia having no claim over the land. The US went on to impose an apartheid regime which has deprived generations of Indigenous Peoples their right to self-determination.

The Hawaiian Kingdom, an independent nation still recognized in formal treaties with over 170 countries, saw its rightful government overthrown in an unlawful, US military-backed coup in 1893.

The United Nations (UN) recognized Alaska and Hawaii as territories under US colonial occupation until 1959.

Their designations only changed after illegitimate statehood referendums in both places which allowed white colonists and US military members to vote, in violation of international standards.

Today, Indigenous Alaskans and Hawaiian nationals are marginalized on their own lands and suffer stark racial disparities in wealth, housing, health, food access, and the criminal legal system.

Indigenous Alaskans and Hawaiian nationals fear further contamination

Longstanding racist policies have left Native peoples more vulnerable to the ravages of the climate crisis, as the US government and American businesses continue to extract Alaska and the Hawaiian Islands' rich natural resources for their own profit.

Fossil fuel production, the commercial fishing industry, and US nuclear weapons testing have led to gross levels of environmental destruction in Alaska and made it hard for many Indigenous Peoples to maintain their traditional subsistence activities.

Ambassador Ronald Barnes, the official representative of Indigenous Alaskans at the UN, recalled how a 1971 underground nuclear blast on Amchitka Island resulted in higher cancer levels in his Bristol Bay fishing community and mysterious holes and sores in the salmon.

Barnes said analyses show ocean currents will carry the Fukushima wastewater from Japan to Alaska before it moves out into the Pacific. He worries that nuclear contamination could once again hurt whales, wild-stock salmon, and other traditional food sources and have negative health effects for Indigenous Peoples.

Hawaii, meanwhile, has seen US commercial agriculture businesses gobble up enormous swaths of terrain for sugar and pineapple plantations, leveling forests and poisoning the stolen land with harmful herbicides and pesticides. Today, Hawaii imports around 90% of its food, which is both unsustainable and unnecessary given how fertile the ground is.

On Oahu, activities on US military facilities – which occupy 22% of the island – have left drinking water contaminated, all while endangering the national security of the Hawaiian people. The mega-tourism and real estate industries have only made matters worse across the islands.

The influx of wastewater from Fukushima is raising fears of increased damage to Hawaii's beaches and marine wildlife as well as the health of its people.

Lack of scientific data raises concerns over potential environmental harms

Long victim to environmental exploitation by foreign occupiers, Hawaiian nationals and Indigenous Alaskans are now being told to trust the Japanese government's Fukushima safety assessment – without substantive evidence to back it up.

Many scientists and human rights experts have joined Alaskan and Hawaiian representatives in sounding the alarm.

"Our concern with Fukushima and the discharge of contaminated water is that we don't know exactly what is going to happen," said Alfred-Maurice de Zayas, the first UN Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order.

De Zayas noted that under the Convention on the Law of the Sea, Japan and other states have the obligation not only to avoid irreparable harm to the oceans but also to take proactive measures to protect and preserve marine environments.

Releasing potentially unsafe, radioactive water into the Pacific could have disastrous results for people and wildlife. Waiting to prosecute crimes of ecocide after the fact isn't good enough, de Zayas added, because by then, "the damage is already done."

Hisashi Saito, who represents the sustainable development educational organization iuventum at the UN, also expressed concerns about the scientific difficulties in determining whether future environmental harms trace their roots to the Fukushima wastewater. This could make it even harder to hold those responsible accountable for the damage.

"They do this because they know it won't be traced so easily," Saito explained. "In the future, they will dump worse and worse nuclear fraction from Fukushima, and they will dump worse and worse stuff from other nuclear facilities – and not just Japan, but the entire world."

"As a Japanese citizen, I feel ashamed that this happened, and I really have to say sorry," he added.

Indigenous Alaskans and Hawaiian nationals demand a seat at the table

The real dangers posed to Indigenous Alaskans, Hawaiian nationals, and Pacific Islanders make it all the more urgent that they have a say in deciding whether or not to release the radioactive wastewater.

"We just really stand in solidarity with the rest of the Pacific, and we are making an appeal to Japan to stop the discharge of the water until there is actual proof – verifiable proof – that the water is actually safe," Siu said. "Without that, we oppose the discharge of these contaminated waters in the Pacific Ocean."

Representatives of Indigenous Alaskans and the Hawaiian Kingdom are working together to win proper recognition at the UN as sovereign peoples under illegal colonial occupation.

Doing so is ultimately an existential fight, as the threat of ecocide looms from powerful nations that do not take seriously the health and safety of Native communities.

"This is a deep concern to us," Barnes insisted. "That's why we assert that we need to be sitting at the table equally as high-contracting parties. We need to be in the decision-making process, and we do not need hegemonic, gun-boat diplomacy [...] where they tell us what's good for us whether we like it or not."

"We want more data. We want more input. We want to have our scientists say what is right or wrong."

Cover photo: IMAGO / Kyodo News